As the subject of climate change has gone mainstream in recent years, companies have come under pressure from consumers and investors to show they’re doing their bit. As a result, many firms have made public their goal to reach net zero or achieve carbon-neutral status.

But, as you might expect, firms differ in their approach: how long, for instance, will they take to reach net zero (2030? 2040? 2050?); what exactly do they mean by “net zero” (just the firm’s emissions, for instance, or the emissions associated with the use of its products?); and how do they intend to attain net zero (by focusing on specific targets to cut emissions or by using measures to offset those emissions)?

The road to net zero, it turns out, has potholes aplenty. And that carries the risk of greenwashing – where firms talk the green talk but don’t walk the green walk.

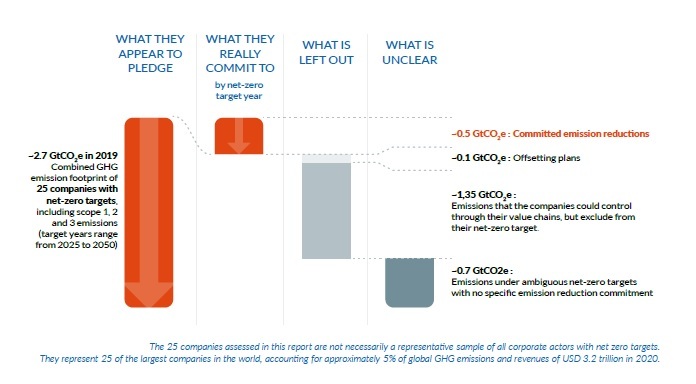

As noted in a recent report by the NewClimate Institute, a climate-focused research body based in Germany, this gap between actions and deeds matters, not least because the world’s biggest companies are responsible for a hefty chunk of GHG emissions. The Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor 2022 looked at 25 major global firms, all of which have pledged net zero, and whose own numbers show they account for 2.7 GtCO2e between them – or 5% of global GHG emissions.

So, how well are those global titans doing in their efforts to be corporate climate leaders? From the report, it seems their efforts could be described most kindly as mixed. While three firms had committed to “deep decarbonisation of over 90% of their full value-chain emissions by their respective target years”, they were the exception. Overall, the 25 firms had specific commitments that would see their collective emissions cut by less than 20% – or 0.5 GtCO2e by the target date that each had set (see graphic below).

The integrity of corporate net-zero pledges

Greenwashing 101: How to avoid it

One doesn’t need to be a maths major to know that 20% is a long way short of the 100% that net zero implies. Somewhat inevitably, this sizeable gap raises the charge of greenwashing (though it’s also true that, as the 25 firms have goals to cut emissions, they at least recognise the importance of being seen to take action).

Helpfully, the report lists four good-practice areas that all firms harbouring net zero ambitions should focus on to avoid the faux-green label. Briefly, those are:

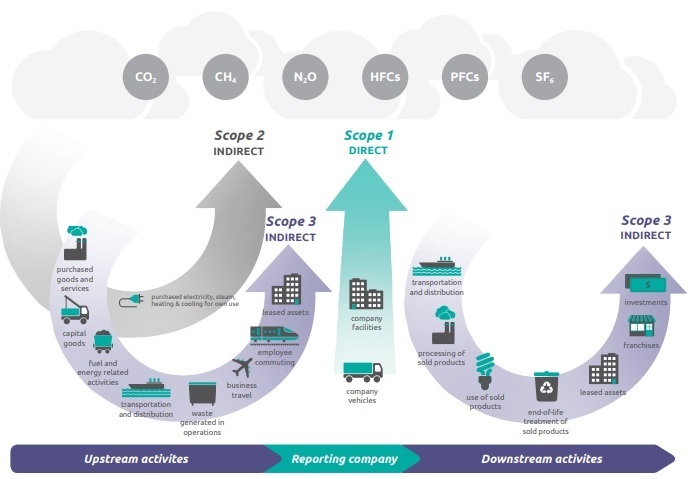

- Comprehensively track and disclose the firm’s GHG emissions each year, with emissions data split between Scope 1, 2 and 3 (see graphic below).

- Set specific targets for each emissions class, don’t mislead people about them, and ensure those targets are independent of offsetting efforts (more on that shortly). The first target date should be within five years.

- Reduce emissions by using deep decarbonisation measures and by sourcing the highest-quality renewable energy possible.

- Be ambitious in terms of financing climate change mitigation measures that extend beyond the value chain, and steer clear of misleading claims or pledges about offsetting.

Carbon offsetting, which has proven controversial and contentious, comes in for a fair bit of criticism. That’s because much of the time, it relies on nature-based solutions like planting trees; however, at some point those trees will die, which means this approach merely delays the release of carbon. And, the report notes, climate change success requires that the world cut emissions and increase carbon storage, so focusing on just one is missing half the picture.

Emissions – Scope 1, 2 and 3

Actions vs words: How to win the “Race to Zero”

The 25 global companies in the report are far from the only firms pledging net zero. The UN’s climate body, the UNFCCC, has a campaign called the Race to Zero, to which more than 5,000 businesses have signed up (as have countries, cities, universities and large investors).

For the thousands of businesses stating publicly that they are on board to reach net zero by 2050, and for the thousands more joining the Race to Zero each year, the report contains useful lessons. As we’ve seen, much of this revolves around the gap between what firms pledge and what the examples of best practice indicate they are likely to achieve.

As the first graphic shows, the biggest gap comes from the emissions in these firms’ value chains – emissions that firms could choose to control but instead exclude from their net-zero targets. This accounts for half of their total GHG emissions.

The other key gap, totalling a further quarter, is the use of ambiguous targets that lack specific commitments to target emissions. (As the saying goes, you can’t manage what you can’t measure.)

In other words, if firms are serious about their net zero pledges, they need to be ambitious in setting their emissions goals – and they must publicly define their targets and report on how well they’re doing. Actions, after all, speak louder than words.

At the same time, firms need to have short-, medium- and long-term targets. Setting a net zero target for 2050 is all very well, but that means accountability is decades away. That might be convenient for firms interested in a spot of greenwashing, but it’s hardly best practice.

And lastly, firms in sectors whose products are used by others – vehicles, say, or electronics – need to factor in cuts to the emissions that come with the use of those products. Currently most don’t, and these so-called Scope 3 emissions (a category that also includes other emissions related to upstream and downstream activities) comprise a large part of the gap for the firms in the report. This presumably holds true for many other businesses too.

In summary, then, while companies should be applauded for publicly committing to a net zero future, they need to be honest and transparent about those goals. Failing to do so leaves them open to the charge of greenwashing which, in this era of heightened focus on environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues, could cost them. The goal of the Race to Zero, after all, is to cut their corporate emissions to zero, not their credibility.

World-class communications strategy and execution

Contact us to get started